How to Talk About Collared Shirts

I wrote this very long guide to help you understand everything you want to understand about shirts. I don't expect you to read the whole thing, but if there's anything you want to know about shirts that you don't see in here, please, let me know!

My cousin's son has a lot of henleys in his closet. I asked him why, and apparently, his private school has a dress code that requires a buttoned shirt. This is a stupid dress code. Not because all dress codes are inherently bad, but because they picked the wrong words for the policy. They clearly intended to limit students to collared shirts, which are a clear category ranging from smart casual up. A henley is just as casual as a tee shirt, so all this dress code accomplishes is that it annoys students and their parents. (Alternatively, they could have meant to limit the dress code to woven shirts, but knit collared shirts are cool and I'm going to talk about them).

Whether you're a guy trying to dress better, or a school principal trying to design a better dress code, this guide is for you! I'm going to go through a variety of collar styles, fabrics, weaves, and other details, teaching you all sorts of vocabulary—both the kind you absolutely need to know, and the kind you don't really want to know at all.

You don't need to read through this guide start to finish in one sitting. You might want to look for the sections you think look interesting, or bookmark the article and use it as a quick reference. On the other hand, if you're trying to do research for made to measure or bespoke shirts, skimming the whole article and stopping at the parts that pique your interest might be a good idea.

- What is not a ccollared shirt?

- What is kind of a collared shirt?

- How to talk about shirt collars.

- How to talk about shirting fabrics.

- What other style details differentiate collared shirts?

- How to talk about shirt fit.

- How to talk about shirt paraphernalia.

- Alright, now which ones should I buy?

What is not a collared shirt?

A tee shirt is not a collared shirt. I mean, technically, you can argue that the little band at the top of the tee shirt is a collar, but you shouldn't argue that, and nobody who says "collared shirt" means to include a tee shirt. Tee shirts can have crew necks, v necks, or scoop necks. Collared shirts are typically also made from different fabrics, although there are corner cases here I'd rather not get into until later. Tee shirts are generally made from jersey, a knit fabric.

A henley is not a collared shirt. A henley is just a crew neck tee shirt with a few buttons going down from the neck, but not all the way down. It is similar to a popover, except a popover has a collar, and a popover usually uses similar fabric to a collared shirt, whereas a henley is usually still jersey.

A sweatshirt is not a collared shirt. It's similar a crew neck tee or sweater, except with a very particular fabric, which you will probably never see on any shirt with a collar. A hoodie isn't a collared shirt, either. No, a hood is not a collar, and the fabric is still wrong.

A sweater is not a collared shirt. Knit shirts exist, and the distinction might get hazy at some remote point, but shirts usually use thinner materials and sweaters often have elastic/ribbing at the hem because they are meant to be worn untucked. So I'll say a knit shirt is distinct from a sweater or cardigan.

As for collars... there are sweaters with a "shawl collar," but... That's normally diferent from the shawl collar you'd see on even a knit shirt. A "shawl collar" or shawl neck pullover might use toggles. The shawl collar on a cardigan is really more like a lapel than a collar. Also, both of these are much thicker than any knit shirt would be. So yeah, a sweater is not a collared shirt.

What is kind of a collared shirt?

An overshirt, also known as a shirt jacket, to the extent that it is a shirt, is a collared shirt. But it's kind of outerwear. They usually have pockets, including some types of pockets that other kinds of shirts don't have. Let's not dwell too much on overshirts, other than to remind ourselves that they exist.

Again, some sweaters have collars. And you can, if you want to start arguing about definitions, call a sweater a shirt. But I won't. So a sweater is not a collared shirt.

Shirts with Band, Grandad, Nehru, and Mandarin collars are, as far as I'm concerned, collared shirts, simply with minimal collars. I'll discuss them more in a bit.

How to talk about shirt collars.

Collar Construction

A collar is generally a separate piece sewn onto a shirt. This is not always the case—see One Piece Collar below.

There is often a collar band on a collared shirt. This is generally a band that goes around the underside of the collar that helps it stand up. The collar band often covers the seam where the collar is attached to the shirt. Take a look at some of your collared shirts, under the collar, and you'll very likely see a strip of fabric there. Collar bands are often important to the structure of a collar. They make a very noticeable difference with polo shirts; the collars without collar bands tend to collapse in a washing machine, wherewas the ones with a collar band tend to stand up better over time. That's not to say that a collar band necessarily makes a shirt better.

A one piece collar is a type of collar that is not stitched on, but is actually a single piece with the shirt, woven or knit continuously, and does not use a collar band. This allows it to create a smooth, soft roll the whole way through. Most of the other collar styles here can be one-piece collars, but these are relatively rare, as it is hard to sew a shirt together like this, and also hard to make a fabric and fusible combination that rolls just right. I believe that the term capri collar also refers to a one piece collar, but this is not very clear from my research.

Fusible or fusing is... Uh, it's confusing. Essentially, the collar itself is usually two layers of fabric, and there's usually some kind of gluey "fusible" lining in between them. This helps determine how stiff the collar is, and how it rolls. Some shirts don't use any at all, which makes them extremely flexible—since this unlined collar is just made of regular cotton. Some very high-end shirts use a floating lining here, similar to a floating canvas in a suit, but this doesn't make much difference, and even top-end brands like 100 Hands use fusible by default. Fusible can be ironed to a collar with a hand iron or pressed by machine—usually the latter. Simon writes much, much more about collar lining here.

Sometimes, on a button down collar, the actual length of the collar points (to the button hole) is longer than the height from the button to the top of the collar. This can call the collar to roll in and out in a certain way. The details of collar roll depend on the size of the collar (the length of the points, the height of the collar above the collar band or above the buttoning point, the proportions and shape of the collar, the lining used used, the button position on a button down collar, the fabric specifics... There are a lot of factors here. As with a lapel roll on a jacket, a collar roll is something menswear aficionados go crazy for. I discuss it further below around button down collars.

How to talk about collar styles

I took enough of these images from Proper Cloth that they earn a special shout-out. It's nice to be able to compare likes with likes.

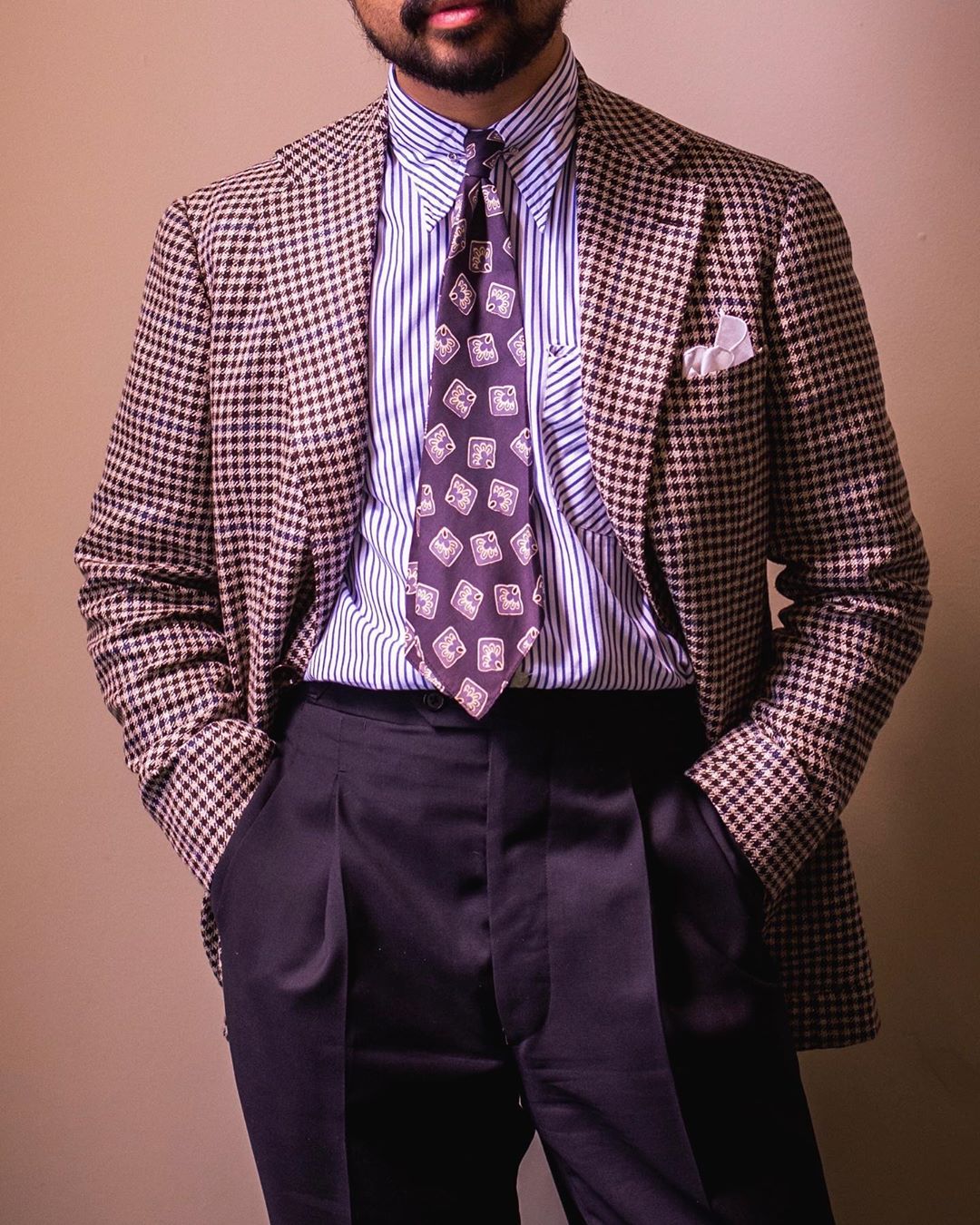

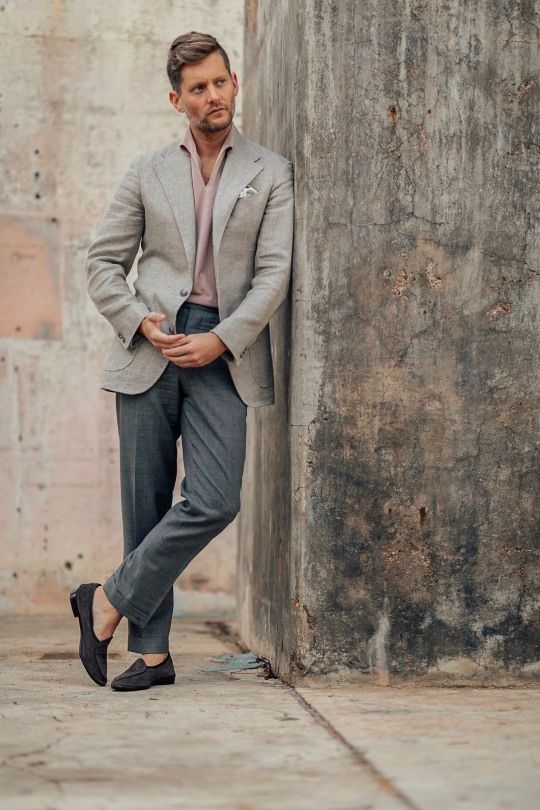

A Spread Collar (tie, open) might what you think of when you think of a "regular" shirt collar. Either that, or you're thinking of the Semi-Spread Collar (tie, open), which might be a little narrower and look better without a tie. Or a Point Collar, or Forward Point Collar (tie, open), which might be taller and narrower still. Consider these all in proportion to your face height and width, tie knot width, and lapel width and position.

Some people define spread and point collars by specific proportions, but the numbers vary, and the important thing is just that you're thinking about proportion.

Of these, the spread and semi-spread are the most modern, and the point is the most classic. The wider the spread, the wider a tie knot you can use. A point collar can look great when going for a classic vibe—at the extreme, consider the spearpoint collar, narrower and longer, and related to the tab collar I'll discuss below. Ethan Wong loves the Spearpoint Collar. Pair it with a collar bar and vintage tie, and you'll make him proud.

Generally speaking, I believe narrow tie knots (like the four-in-hand) are better; the four-in-hand is the only knot James Bond wears, so no, you are not to good for it. Accordingly, I tend to prefer longer, narrower collars, which frame narrow knots well.

You will generally want to keep the collars above pointy with collar stays.

All of the above come to a point on each side, button in the middle... Let's explore what isn't a spread or point collar, shall we?

Although the spread and point families might be simpler and more common, a Button-Down Collar (tie, open) is probably your bread and butter, especially if you're not wearing ties every day. The "oxford cloth button down" is your classic "smart casual" shirt—generic, good enough for a country club, good enough for your office, good enough to wear to a bar. Good at a tucked or untucked length. Okay with a tie. A button down collar is pretty standard on linen shirts and flannels as well. I know, I know, you want to talk about fabrics now, but all things in time.

Right now, I'm going to remind you about all that stuff we said about fusible. Remember fusible?

Because the button-down collar has two fixed points on each side—the top of the collar and the button point—this is the perfect style of collar for a good collar roll. A short, cheaply made button down collar might not have an impressive collar roll. But as you start to spend more, this is one of the benefits you'll see. See: Abercrombie (fine for the price, but an awful collar in person), Brooks Brothers (the classic, but buy it on sale), Kamakura, Gitman Vintage, Jake's.

Some brands make a hidden button down collar, where the collar covers up the button and buttonhole. These stay put and roll like an OCBD, but look like a spread collar to those not paying attention.

A cutaway collar (tie, open) is similar to the full spread... but even wider, cut away from the tie. If you wear these with a tie, it will show a bit around your neck. On the other hand, there are those in Italy who wear these wide open without a tie. If you have one, play around, see what you like.

A club collar (tie, open) is like a spread collar except, instead of coming to a point, the "points" are rounded. I choose to believe that this was the inspiration for the iPhone's icon shape. These collars are kind of old-timey country club things, again made for a tie. It's one of the harder ones to wear well today—although it's possible.

A Tab Collar (tie, closed, no tie—for illustration purposes only) is a funny one. Do not wear this without a tie. That little strip of fabric you see in the second photo is the "tab." It buttons behind your tie, and is supposed to lift it up, in a manner similar to a collar pin. It's cool if you want your tie to sit in a particular way, and you can't pull it off with just the tie, and you don't like collar pins, this is one way to do that.

A camp collar or Cuban collar is an open collar that generally does not have a collar band. Instead of standing up or rolling, the camp collar lays open and flat in a distinct, casual way that does not allow for ties. There is sometimes a loop on the lower point on the buttonhole side of the collar, which could in theory attach to a button on the opposite side, but probably won't.

This casual style often makes for a great short sleeve shirt, and many fun, patterned shirts use a camp collar. Pajama shirts also often use the camp collar. Interestingly, a Guayabera shirt, despite being a formal shirt, uses a camp collar. This is discussed in more detail below.

A camp collar can, but does not necessarily, come in a one piece constrcution. I think that capri collar specifically refers to a one piece camp collar, but I am not sure. I've also seen a camp collar referred to as a "revere collar," but can't find a definitive source on that either. And I've also seen it referred to as a resort collar or vacation collar, but those are pretty much just made up names that a few brands used for cheap marketing. Wikipedia also lists "convertible collar" and "notched collar" as names for the collar, so... Well, try to call it a camp collar.

The term "convertible collar" is generally used to refer to a shirt that's cut so that it can be worn as a camp collar or a spread collar. Sometimes, yo ucan just take a spread collar, smash it into the shape of a camp collar, and kind of get a similar effect, but this usually only works with collars that are designed to do both.

If you hear the term runaway collar, a person is most likely referring to any of the above collars worn with a jacket in such a way that the collar falls over the tailored jacket. Sometimes, people do this by accident, and it looks bad. Sometimes, people do this on purpose, and it looks good. A camp collar, because it naturally sits open, is a good way to experiment with the intentional runaway collar. I have an album of photos of runaway collars here.

A band collar (closed, open), also known as a grandad collar, is... Just a plain strip of fabric around the neck. There's nothing rolling or folding over the band, it's just the band. The band goes all the way around the neck, buttoning in the center—this is distinct from the Nehru or Mandarin collar below. This collar, since it obviously cannot support a tie, is obviously casual. You may see it in popovers. It's not very common.

A mandarin collar, also known as a Nehru collar, is similar to a band collar, except that there is a gap in the middle where the button might go. The collar buttons below that gap. This collar style is not only used on shirts, but also in a "Nehru Jacket," an Indian equivalent to our suit jackets.

The "mandarin" collar is named for mandarins, a particular sort of... official scholar / bureaucrat in China... well, the etymology is long and weird, but there it is in case you care. It later earned the name Nehru collar from Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru—however, he usually wore jackets—"Nehru Jackets"—with this kind of collar, and that's usually how the term "Nehru Collar" is used—"mandarin" is both the older name and the name more appropriate for shirts.

A Wing Collar is a funny thing. Trying to describe it... It's kind of like a stiff band collar with a miniature spread collar sticking out at the front. Just two small flaps. This collar accommodates a bow tie, and is pretty exclusively meant for tuxedo shirts—see the discussion of eveningwear below.

A Shawl Collar technically exists, but it's hard to find on a shirt. This one is from 100 Hands. You'll see shawl collars more often on knitwear, although a "shawl collar cardigan" is a little different, the shawl there is more... lapel-like.

As a final note, most of these collars can be a contrasting collar—a different color/pattern from the rest of the shirt. A contrasting collar is most often white. You could also get a contrasting cuff or placket.

Contrasting collars come from the days of detachable shirt collars—since your collar gets dirty faster than everything else, people used to detach them from their shirts to be washed separately. If you buy your shirt collar separately, you will probably go for a versatile color—solid white. This was a big deal—Troy, NY was the fourth wealthiest city in the US, and was known as the "Collar City" for manufacturing these collars. Yeah. Weird.

How to talk about shirting fabrics.

A shirting fabric is a yarn of some material, woven or knit in some pattern. When choosing your fabric, you might not only want to consider material and weave, but also weight, ply, and of course, color and pattern. Note: the terms "shirting," or "jacketing," or "suiting," specifically refer to fabric.

Fair warning: it's hard to convey what's good about a fabric in a photograph, so you're about to stare at a wall of text. You don't want me to show you what cotton looks like, that's not helpful.

Common Shirt Materials

Cotton is your basic shirting material, covering a huge variety of both dressy and casual shirts, and easily the majority. It's cheap, light enough, and soft enough. It can be woven in a million ways, each of which provides a nice textural contrast to a wool suit and silk tie. When I discuss weaves below, almost all of them will usually come in cotton.

Cotton is sometimes treated in a variety of ways so that it does not require ironing. Some of these treatments involve formaldehyde. That sounds scary. However, aside from potential comfort issues, these treatments are perfectly safe and should not scare you. The amount of formaldehyde on the garment, even before its first wash, even in the worst case, is negligible, and would not be absorbed by your skin anyway. That said, different treatments can sometimes irritate the skin, and personal preference can play a big role here.

Linen, which is normally woven in the linen weave, is a little bit less versatile. Okay, it's much less versatile. A pure linen shirt is almost always casual—people will wear them as dress shirts in some climates, but there's a bit of a problem.

Linen wrinkles. It wrinkles like crazy. Fashion photography is really bad about this—you'll see a lot of fresh linen that was opened, maybe ironed on the spot, and worn carefully so as to not show the fabric's true nature. But if you want your shirt not to be wrinkled while you're wearing it, you are going to have a problem with linen.

On the other hand, if you're willing to embrace the wrinkles, linen can be amazing. Quality linen starts off soft and gets softer over time. It's light, and breathable, to the point of keeping you amazingly cool.

I love linen. But it's not for everybody.

Linen is made from the flax plant. If you see people advertising a "flax" shirt, that's linen.

Ramie and Hemp are rarer fabrics kind of like linen. Ramie is a little coarser and probably doesn't age as well, but it's probably cheaper than linen. Hemp is probably closer to Linen. Hemp fibers are very long though—about twice as long as linen fibers. This makes hemp strong enough that it is often used to make rope.

Wool is a miracle fabric, but not the standard choice for shirting. Whether this is because of the expense, or because cheap wool can be itchy, or because it doesn't provide a textural variation with suiting, a few companies are trying to challenge the default, and promote wool shirting, often as an alternative to performance shirting.

Wool is breathable and soft. It has natural anti-microbial and anti-wrinkle properties, helping avoid the need for non-iron treatments. It can obviously be warm, but still breathable, so it can actually be comfortable in warm temperatures, depending on the specific weave and weight of the fabric.

Flannel is a fabric that might be made from a brushed cotton or wool, often in a poplin or twill weave, and often (but not necessarily) with certain patterns named after the fabric. Yes, this definition is murky.

Rayon including viscose, modal, micromodal, lyocell, and cuprammonium rayon or cupro, is a cool fabric for casual shirting. It's a synthetic silk-like material great for camp collar shirts and loud prints. Although it's synthetic, rayon is made from plant fibers and has some qualities in common with natural fabrics, so it is considered "semi-synthetic" by some.

Modal is more like cotton than the others. Each form of rayon has some unique properties. I encourage you to study them separately if you are interested. Tencel is a name-brand formulation of lyocell—I like Tencel. Bemberg is a name-brand formulation of cupro usually used for jacket lining, usually not for shirts.

Some people advertise bamboo as a shirting material. That's one of the plants they use to make rayon. However, bamboo can also be formulated into a linen-like fiber. It's really not the most useful word for describing what a shirt is made of, except for marketing teams who think it sounds cool and sells shirts.

For shirting, Silk is an extreme luxury fabric. It has a sheen that is... dangerous to work with, but also a beautiful drape and unique comfort. The main problem, aside from quality silk being expensive (and potential ethical issues), is that caring for silk is rather difficult. It may be more expensive to have cleaned than wool, and might need such cleaning more often, and might not last as long. If you go this route, good luck. On a practical level, rayon might be a better idea, more comfortable and easier to handle.

Polyester is probably bad. Cheap bargain bin shirts will either be made of polyester or cotton, and cheap polyester is probably worse than cheap cotton. Many "performance" brands will use polyester... mostly to save money, but realy not deliver anything special. Sometimes you get some wrinkle-resistance or stretch, but it's usually not all that special. However, a few performance shirtmakers will use specific formulations of polyester that actually do have some upsides. Again, this is a situation where you have to do a lot of your own research—most of what you'll see out there is marketing nonsense, so look for reviews on platforms like Reddit where you can get around the marketing and dig into the facts with thorough comparative reviews and people who understand these materials deeply. I personally prefer cotton over any of these performance blends in all contexts.

Polyester can also be used to make fun printed shirts, like those made from rayon. Rayon is generally a better pick, but polyester is not necessarily the worst thing to wear in this context.

And of course, all of these materials can come in blends. Linen blends are smart, as they can help you keep cool without excessive wrinkling. Silk can be an expensive component but still provide comfort and drape as part of a blend. Polyester or nylon might be used in performance blends for good reasons, or for cheap reasons. Many brands will advertise their own proprietary "performance" blends—to some extent, these blends are formulated to keep costs low, and to some extent, they reflect valuable properties.

Elastene, also known as Spandex or Lycra, is a synthetic, elastic fiber often blended into other fabrics in order to make the fabric stretchier. This can be useful if your shirt is too tight, and you want to wear it anyway, and you want to move freely in it. However, elastene loses its elasticity after a year or two, and sags in an unsightly way. Instead of buying a shirt that is guaranteed to become garbage that fast, I would recommend that you buy a shirt that fits you from a half-decent fabric, instead. Cotton should not be hard to find.

Shirt buttons are usually either made from a plastic resin or mother of pearl, although they can someties also be made of corozo or coconut. Metal snaps can be used, too, often with mother of pearl adornment ("pearl snaps"). I'll talk more about buttons (and some alternatives to buttons) below.

Detail stitching and the threads used to stitch on buttons might be, and often are, different materials from the shirt body. Almost all garments, no matter how high-end, use polyester thread in some stitching, somewhere. It's not only cheap—it's strong, and lasts forever. Note, however, that because shirts often use a variety of materials, and those materials shrink differently when treated by heat, you should avoid that heat in all contexts—washing, drying, steaming, and ironing are all risky if you're using any heat at all.

Common Shirt Weaves and Knits

There are three fundamental Weaves—plain weaves, twill weaves, and satin weaves. On top of that, there are some special weaves that are a little more interesting. And after that, we'll have to talk about knit shirting. So let's dig in.

Note that a lot of guides include photos of the weaves here, which... I don't think is very useful. You don't care how the fabric looks under a microscope, you really care how it feels and behaves. Unfortunately, that means you're about to see a wall of text. I'll do my best to break it up.

Plain Weaves.

Both sides of a plain woven fabric are the same. You don't want me to explain this in any more detail—believe me, I tried, it was awful.

Poplin is a light, simple weave, good for dress shirts because it doesn't wrinkle much. Broadcloth is the same weave as poplin, except generally dense, and probably even better for dress shirts. End-on-end is poplin, except one of the threads is white and another is colored, so the alternation creates a certain visual effect. Chambray is a blue and white end-on-end, except usually a little heavier, but still pretty light and breathable.

Oxford is a "basket weave," which is a type of plain weave. It creates a fabric that is usually thicker and heftier than most poplins and twills. Traditionally considered casual, you can still dress oxford up with a blazer and tie—or dress it down and wear it alone. Oxford Cloth is one of the ingredients in the classic "Oxford Cloth Button Down," or "OCBD" a commonly recommended staple in basic wardbobes. Pinpoint Oxford is a little denser and a little more dressy.

Royal Oxford aka Imperial Oxford is actually very different in effect from the other oxfords. It's a textured, dressy, luxurious fabric, that might be better compared to broadcloth than oxford.

Linen. Wait, am I in the wrong section? Nope. There's a plain weave called the linen weave, and it's probably the weave used for your 100% linen shirts.

Taffeta and Shantung are plain weaves usually used for silky fabrics, and thus not super relevant to shirting.

Twill weaves.

Unlike plain weaves, the two different sides of a twill weave have somewhat different textures. These sides might be called the face and the reverse ("other" side or "inside" of the fabric). A fabric could be warp-face or weft-faced, but I'll leave you to dig into that.

A simple twill can be similar to Poplin, but it's a little less breathable, and softer. Still quite good for dress shirts.

Herringbone is twill, except, like End-on-End, it involves alternating colors, creating a zig-zag sort of pattern—this is technically present in the structure of all twill weaves, but not necessarily visible.

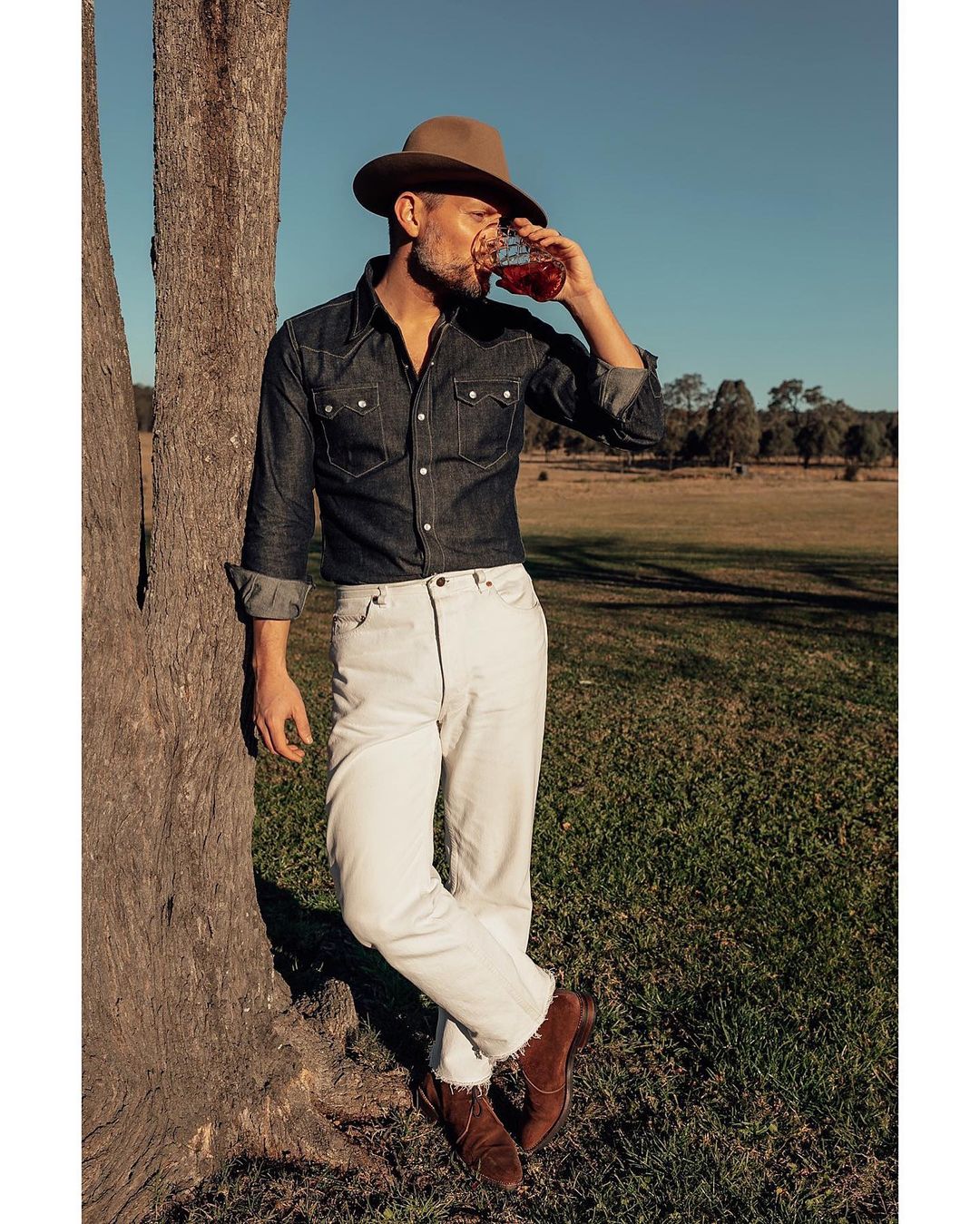

Denim is a twill fabric in alternating indigo and white threads—again, consider the difference in texture (and color) of the face or outside of your jeans as compared to the reverse or inside.

Shirts come in denim, too! It's more wearable than you might imagine. Obviously, denim shirting is quite casual.

Formally, the definition of denim involves a lot of indigo threads crossed with a few white ones, so black, white, and other colored denim are technically not denim. If you want to read more about denim, consider looking up the differences between left-hand, right-hand, and broken twills, or the differences between raw and washed denim, or sanforized nad unsanforized.

To help illustrate, chino is a twill fabric, but not one that would be used for shirting.

Satin weaves are the third archetype after Plain Weaves and Twill Weaves. Satin fabrics, like twill, also have a warp and a weft face that are distinct. One of the faces often has a certain sheen to it. A satin fabric can be double-faced, in which case both outer sides might have that sheen.

Charmeuse is a type of satin weave with the high-sheen face on one side, and a dull "reverse."

When cotton or other non-silky fabrics are woven in a satin weave, the resulting fabric is a sateen.

Moleskin is a satin-woven pile cotton fabric usually used for trousers, but moleskin shirts do exist.

Piqué (pronounced pee-kay), aka Marcella, is a weave commonly used in polo shirts, but also specifically required for white tie shirting. For context, white tie also requires a marcella bow tie and marcella waistcoat. piqué can also be a knit, and I've heard it said that all polo shirts are, by definition, knit, but I don't really know the difference between knit piqué and woven piqué, so if somebody can fill me in...

Seersucker is a weird weave often used with cotton. It produces a fabric with ridges similar to corduroy, but instead of being a pile fabric, it's a crisp, light, breathable one.

Jacquard is a fancy method of weaving or knitting fancy patterns into shirts. I think jacquard weaves are, therefore, unique. Dobby is similar, produced on a dobby loom instead of a Jacquard machine.

Flannel is both a pattern and a fabric, but more formally a fabric. The fabric is woven from brushed, napped, or sometimes just loosely woven yarns, and is thus very soft. It is used for casual shirts and pajamas, among other things. Wool flannel can be used for suiting, too! The check pattern you might think of as flannel is discussed below.

Tweed is not a common fabric for shirting—it's usually a thick, heavy wool fabric used for stuffy old blazers—but 18 East and other brands are putting out cotton tweed shirting now, so fuck, I guess I have to talk about it. That said... It can be a plain or twill weave. It'll often be a soft woolen herringbone, but... I can't pin it down to one specific defining characteristic.

Pile fabrics are those like velvet or corduroy where a cut end of the yarn faces outward. This creates a sort of unique and intense softness. Such shirting is uncommon, but corduroy shirting is showing up a little more here and there—it's worth considering. You might find a corduroy overshirt appealing. Again, moleskin has a slight pile to it.

Knit fabrics are less common in shirting. There's a cool italian vibe to a knit shirt. I think they're coming back. Polo shirts are easier to find in a knit fabric than full button-ups, but knit button-ups are becoming more and more common.

Jersey is a type of knit mostly used for tee shirts. However, rugby shirts are also made of heavy jersey. A few other brands like Ring Jacket make buttoned, collared shirts from jersey. This one looks dressy, but probably feels unreasonably comfortable.

Some guys really love patchwork—different fabrics sewn together, sometimes in totally different patterns. It echoes the spirit of mending worn clothing. Madras, discussed below as a pattern, is sometimes made from patchwork. Boro is a Japanese form of patchwork that is meant to be noticed, often used in conjunction with sashiko, which involves visible needlework. Mending, in these art forms, is a meaningful act. They appeal to the spirit of cherishing an old, beloved garment rather than throwing it out. This is obviously a sustainable practice.

Patchwork may be done with scraps of old fabric, sometimes torn from an old shirt. On the other hand, high fashion brands might make patchwork clothing new, from scratch, with all new pieces, to simulate a worn and repaired appearance—that is obviously not as sustainable a practice.

How to talk about common shirt patterns

Plain / Solid. I don't need to tell you what a solid color is. You should have at least one of these shirts in white, and at least one in blue, but probably more than that. I like pastel pinks and purples, too.

Subtle textures might still count as solid, or might be referred to by the name of their weave in some cases—particualrly when those weaves use different colored threads.

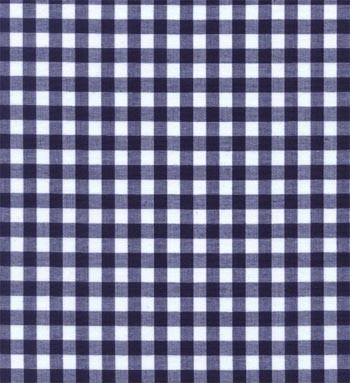

Checks are basically any pattern that repeats in horizontal and vertical lines, particularly the following. Plaid can technically refer to any check, but is often used to imply a tartan check.

A graph check or windowpane check is probably your basic check—thin horizontal and vertical lines, often on a white or off-white platform. If the vertical and horizontal lines are different colors, you have a tattersall check.

A Gingham Check, instead of thin stripes on a shirt that's mostly background, the stripes are equally thick to the space between them, so that you have squares of background, squares of the stripe color, and squares of the intersection. Blue and white gingham is extremely common (but is not necessarily from J. Crew). A three-color gingham can exist too, which can allow a wider variety of squares to appear. Gingham checks can come in somewhat small to somewhat large scale. A relatively small gingham might be called "micro gingham." A buffalo check is a very large scale gingham check, often in either red + black or navy + white.

A tartan plaid is a complex multi-colored check itting into certain Scotish traditions. The Royal Stewart tartan is popular. The Black Watch or Blackwatch tartan is a traditional green, blue, and black tartan. Burberry is known for its own trademarked tartan, very commonly used on its scarves. Some people actually consider this pattern to be such obvious branding that it's tacky, almost like an Hermes belt.

If somebody refers to "flannel" as a pattern, that person is either referring to a gingham (sometimes buffalo) check, tartan check, or other plaid pattern. That said, flannel fabric can come in solid colors or any other pattern as well.

Madras is a light fabric generally either found in a fun-colored tartan plaid, a more inconsistent check, or a patchwork of fun colors. It is rather loud and can be hard to wear. It's most common in the summer. @acutestyle on instagram and and Gerry Nelson wear a lot of madras—@acutestyle tends to put it forward, while Gerry tends to layer with it in ways that can tone down its natural boldness. "Bleeding Madras" is a form of madras dyed in such a way that colors "bleed" into one another, making the lines between different color portions blurry and muddled.

Permanent Style has a thorough guide on shirting checks here.

Finally, a glen check is a large-scale check pattern over a smaller-scale check pattern. This is uncommon on shirts.

Stripes.

Unfortunately, the language around stripe patterns is much more ambiguous. People will say that a certain term refers to narrow colored stripes on a background, even stripes, thin stripes, thick stripes, stripes of a particular width, vertical or horizontal stripes... But none of this is incredibly clear. The phrases you'll hear include Bengal stripes, awning stripes, and candy stripes. Most of these are vertical stripes, especially on dress shirts. Rugby shirts, which I'll discuss below, often use horizontal stripes. Diagonal stripes are unusual. My best understanding is that Bengal stripes might be vertical, even stripes, usually thin. Awning stripes might be vertical and uneven. Candy stripes might specifically be red and white bengal stripes. But this is really inconsistent between sources. If you want some reference, Permanent Style has a breakdown.

A university stripe shirt is an oxford cloth shirt with narrow, even stripes, usually in white and a pastel color, and usually with a button down collar. It's a pretty versatile style, but specifically used in an Ivy / Prep style context.

A floral pattern is any pattern with flowers. This might look good with short sleeves and a camp collar in rayon to make a good "aloha" shirt. A microfloral is a small-scale flower pattern, and is often used on otherwise dressy shirts by men who don't really know good ways to dress clothing down.

The paisley pattern is a sort of... teardrop amoeba thing. It's a very loud pattern not normally suited to shirting.

Obviously, shirts can come in unique patterns and prints. Here's a repeating print from Knickerbocker NYC. See? Anything goes. Eighteen East engages in block printing and other interesting printing techniques. Printed shirts can be a lot of fun!

That said, remember that unique patterns won't be traditional and aren't good for dress shirts. Again, they're good for fun camp collar shirts.

Pattern-matching refers to the practice of continuing a pattern over a seam—for example, a stripe or check might continue over an underarm seam, from the arm to the cuff, from the collar to the shirt body, or over the placket. This is pretty hard to do. Machines can't do it. You need people to line patterns up carefully, and know how the shirt will move when worn, so you won't usually see this done for cheap.

Finally, we talked about contrasting collars above. Really any piece of fabric can contrast. Patchwork aside, the collar, cuffs, placket, pockets, and yoke could all contrast. A white collar and cuffs might be relatively safe, but you'll quickly enter dangerous territory. Colorful / patterned contrast, contrast on the inside o the collar or cuff or placket, and other unusual contrasts are... not great.

What other style details differentiate collared shirts?

Shirt Closure Layout and Method

You've probably assumed, for a lot of this time, that "collared shirt" means something similar to "button up shirt." But a "button up" shirt has buttons going from the top to the bottom, so that the shirt can open up all the way. Maybe you're bored by this. Surely, there's another way!

Well, of course there is, it isn't rocket science.

Popovers and Polos

A collared shirt whose closure method only goes down partway is known as a popover or a polo shirt.

Usually, a polo shirt should come in cotton piqué, but they come in terry cloth, jersey cotton, linen, silk, and essentially any other fabric you can think of, except that, once you start to use woven fabrics that are not piqué, the shirts are usually called popovers. Polos usually use short sleeves, a button closure, and a spread collar, although, again, any of these things can technically change. Some polo shirts are constructed without a collar band, but this can lead to collars that fall apart on wash, especially on piqué polos and cheap synthetic polos.

A polo shirt made of heavy cotton jersey with a white contrasting collar and cuffs might be called a rowing-blazers-rugby These usually have a body with large horizontal stripes of white and some other color. They often also have a logo of some sort at the chest. This style lies on the casual end of prep style, and some guys love it. It can be a good way to blend sportswear with tailoring.

Polo shirts are an important part of tennis and golf culture. You're generally not allowed onto a golf course without a collared shirt. Some brands make specialized "Golf Polos," which are usually made of "performance" fabrics (as I described above, these are usually just cheap poly blends) and usually come in weird, garish color combinations that only look good to golf people. Please don't wear them if you can avoid it.

Buttonless Styles

Now... Do you need buttons for your shirt? Of course not! What other closure methods might you use?

For one, collared shirts don't technically need buttons at all. You could absolutely have a collared shirt that uses a a zipper, a shirt with a string you can tie, or one that doesn't have any closure method at all.

A polo or popover with no buttons or zippers or closures at all is sometimes referred to as a "Johnny Collar" shirt. Such shirts are usually not full-length openings, obviously, they're popovers. See this no-closure polo from Zing Chen.

Also of note, you can have a shirt with only a single button, as evidenced by this polo from Yeossal (which also features a one piece collar).

Finally, of course, there are tuxedo shirts, which accept studs in place of buttons. It might also take studs in place of a few buttons

A moroccan collar (which might not be a collar at all) has something to do with this conversation, but I don't entirely know what it is, so ask Derek Guy. I think it's a buttonless opening with some kind of internal points... Maybe it's like this, but Derek seems to think it involves some kind of point, so...

Cuff Style

The cuff on a long-sleeved shirt is the strip of fabric around your wrist, and there's more going on there than you may think. You want to think about style, button layout, cut, pleats, and proportion. Keep in mind that a cuff is usually stiffer than other parts of the shirt—I believe it is common to use fusible to make a cuff stiffer.

Most collared shirts have barrel cuffs or buttoned cuffs, which are buttoned, and go around the wrist, layering one over the other with the inside of each facing the wrist. That is to say, you can unbutton the shirt at the end of the sleeve to open it, maybe fold or roll it up. This is what you're used to.

Very dressy shirts, however—and this is more common in Europe—can have french cuffs or double cuffs, which will require cufflinks, and often fold out, against one another, creating a sort of... Well, look at the photo, it's like that. Fancy. Sleeve rotation is more important than usual with French Cuffs for reasons that might be obvious. You can also arrange a french cuff like a barrel cuff, if you want to, but it will be thicker and a little different from a real barrel cuff.

It's also possible to have a closed, sweater-style cuff on a shirt, but this is uncommon, even on a knit shirt.

Let's talk about buttoned cuffs. You can have multiple buttons that range around the wrist—allowing you to tighten or loosen the cuff, say around a watch—or up and down the wrist and forearm. Two buttons right on the cuff can help keep the cuff from turning around itself. Three on the cuff is the signature style affectation of Turnbull & Asser. A button further down the forearm can help give you control when folding or rolling the cuff up the arm.

A buttoned cuff can be cut rounded, squared or straight, or mitered. This is honestly not that interesting. If you don't want to think, go with a rounded cuff.

Since the arm of your shirt is probably smaller than the cuff opening, and since the cuff is probably a different piece than the rest of the sleeve, you should generally expect that the sleeve will be folded or pleated to fit into the cuff.

Finally, do think about proportion. A longer cuff cuff doesn't just look different, but folds and rolls differently from a shorter cuff. Cuff circumference, sleeve length, cut, and number of buttons are all things to consider relative to cuff length.

Placket Style

You know that strip of buttonholes going down one side of your shirt? That might be what you call a placket. If there's nothing going on there, you might say there's no placket or call it a French placket, which I guess is what happens when a placket surrenders halfway through being a placket. Casual shirts sometimes have no placket. But usually, there's an extra strip of fabric around those buttons, reinforcing them and adding a little stiffness via fusible. Plackets can be wider or narrower, with more or less visible stitching. A shirt without a visible placket might nevertheless use fusible to stiffen the area where the placket would be.

Like the closure methods described bove, a placket does not need to run the whole way down the shirt. If it does not, it might be called a popover or polo. Your pants' fly is, presumably, a covered placket.

A covered placket places a layer of fabric over the closure method, IE buttons or studs, so that you only see fabric from the front. This might be used for a tuxedo shirt.

Other Shirt Details

Hem. This is a big one—most shirts either have a longer hem, cut so that you are able to tuck it in—ideal for dress shirts—or a shorter hem, cut almost straight, so that it looks good untucked—ideal for casual shirts. The ideal length for a shorter hem is about the center of your fly, or longer if you're wearing high-rise trousers. It shouldn't show any skin (or undershirt) when you move or sit down.

Sleeve length. First, a shirt can either be short-sleeved or long-sleeved. A short-sleeved button-up might be a bad idea—a long-sleeved shirt with the sleeves rolled up pretty consistently looks better. The big exceptions are polos and shirts with camp collars. A short-sleeved shirt is never a dress shirt. If a shirt has short sleeves, that shirt is casual. The one exception here is a Guayabera, discussed elsewhere.

There are two ways shirt sleeves are measured—from the back of the neck to the tip of the cuff, and from the shoulder sleeve to the tip of the cuff. The former measurement is, roughly, the latter plus half of the shoulder width. Sometimes, on clothing with raglan sleeves, you'll see the sleeve measured from the underarm seam, but this is not very practical as it is hard to account for armhole size.

By the way, in case you see it—you probably won't, in this context—a raglan sleeve is a sleeve that isn't attached at the top of the shoulder, but at the neck. This can improve range of motion, but doesn't allow for any structure at the shoulder. It makes more sense for tee shirts, knitwear, and sometimes overcoats.

Pockets. Pockets are casual details. A dressy shirt ideally has no pockets. A casual shirt might have a left chest pocket or two pockets, but rarely just a right chest pocket. Those pockets might also have buttons, which might make a shirt even more casual—two pleated pockets with two-button flaps would be at home on a "western shirt"—the type of thing a cowboy might wear, which also involves curved point designs around the pockets and yoke... You'll know a western shirt when you see it.

Buttons are usually made of Mother of Pearl or a plastic resin. The buttons and the thread used to sew them on can blend in with the shirt and its placket, or they can contrast. Mother of pearl is generally a milky white-ish color—this, plus white thread, usually plays nice with a white shirt, and usually contrasts with dark or very colorful shirts—obviously.

Additionally, buttons can be made of Corozo, a material made from the Tagua nut, or coconuts. Coconut buttons are most often used on "Hawaiian"-style shirts.

Some shirts, especially western shirts, might use metal snaps instead of buttons, in many cases pearl snaps with mother of pearl embellishments on top.

The back of the shirt is more interesting than you might think. The top panel connecting your shoulders is called the yoke. The yoke can be a split yoke, which means that there is a seam separating the two sides of the panel for a little bit of added mobility. Better yet, there might be a box pleat there offering a little range of fabric to really help your range of motion.. The back of a shirt might also just be one clean, solid piece—no yoke, just solid shirt.

Sometimes, there's a button on the back of the collar of a higher-end casual-ish shirt. This could help keep the collar or a tie in place, but it's kind of just for show.

Monograms—usually your initials—are kind of dumb, if you ask me. They can be placed at the cuff, on the body, or... well, anywhere else, if you're feeling funky. The body is considered an Italian style, and generally not to be seen—only get this if you're layering.

How dressy is this shirt?

Any shirt with a short hem cut for untucked wear is a casual shirt, and generally, a casual shirt should have a hem cut for untucked wear. Any shirt with short sleeves, with one very specific exception, is a casual shirt. Any popover is a casual shirt. If you see a popover or short sleeved shirt with a hem designed for tucking, you are most likely looking at a terrible shirt.

If you hear somebody talking about a "sport shirt," that person might be a British aristocrat or a Brooks brother, talking about the optimal shirt for horseback riding, polo, cricket, or some other such nonsense. It might be an oxford, or a flannel, or a denim shirt.

Furthermore, shirts that might otherwise be dress shirts are, if the pattern is loud or strange enough, are casual shirts. Dress shirts should generally come in traditional patterns.

Finally, shirts in casual fabrics are, generally, casual shirts. Oxford and Linen are casual but can be dressed up, depending on the specific community, the weather, and the wearer's skill with an iron. Chambray and Denim are more casual can be dressed up as well, for variety. Dressing up flannel and rayon may be more difficult.

Dress Shirts must always be tucked in. If the shirt is not long enough to stay tucked, then either it is not a dress shirt, or you are a very tall man requiring an unusually long dress shirt.

Formal Shirts are generally those used in eveningwear—back tie, white tie, and equivalents. Some people might use "formal shirt" to be synonymous with "dress shirt," but this is technically not correct.

A tuxedo shirt, has a covered placket, and sometimes pleats or ruffles. For proper black tie, this shirt must be white with a wing collar or spread collar appropriate for showing off a bowtie. It will have a french cuffs and either studs (instead of buttons) or a covered placket. The front might have a bib or a whole bunch of vertical pleats.

For white tie, one must wear a white shirt made of marcella cotton. There are more rules I don't really care about, but I'd recommend looking them up and following them if you want to do white tie.

Technically speaking, a Guayabera, despite being a short sleeved shirt worn as a single layer, is a piece of formalwear. It can be dressed down, but is traditionally worn to weddings and by politicians in parts of the world where suiting is generally impractical. The Guayabera has been described as a "Mexican wedding shirt," but you should generally not assume that it will be appropriate for any particular wedding.

A Guayabera is defined by characteristic vertical pleats—very narrow, usually in two sets of five. It is uaually a white, short-sleeved camp collar shirt in cotton or linen with 2-4 patch pockets, although none of these elements is entirely necessary. Still, if you're trying to use it as formalwear, you want to check as many traditional boxes as you can.

How to talk about shirt fit.

Casual shirts and cheap dress shirts are often measured in alphabetical sizes—XS, S, M, L, XL, et cetera. This only works if your body fits to very standard, common proportions. Some brands expand to include slim/relaxed fits, which is helpful, and long/short lengths, which is good for a casual shirt as you will wear it untucked. You should generally view size charts on these shirts to ensure that the shirt's measurements are consistent with your own. There is no formal or numerical definition of "medium" except as the brand chooses to describe its own sizes.

Off-the-rack dress shirts are usually measured by two numbers: a neck size and then an arm length. For example, I am a 15.5 / 32, as my neck is a fairly average size and my arms are short. Sometimes, you will see the arm length as a range—32-33, or 33-34, et cetera. This does not mean it will fit all men in that range. It's an honest but somewhat unhelpful sign from brands whose QA cannot consistently provide the exact arm length you need. I would tend to demand a precise arm length—brands as cheap as Charles Tyrwhitt can reliably get sleeve length right.

Many brands also offer slim / relaxed fits for dress shirts as well. Shirt length is generally not a concern, as your dress shirt will always be tucked in. If you are confused about that last bit, you've taken a wrong turn somewhere in this guide, and need to read it again. Your dress shirt will always be tucked in.

Shirts can be made to measure or bespoke, in which case the brand in question will customize some large number of measurements including chest, waist size, arm size, armhole size, cuff size, shoulder width, shirt length, possibly even button position—they could make George and Jerry very happy men. When you hear "made to order," that might or might not mean "made to measure." Usually, it means "made with some sort of customization in mind, but not much."

When buttoned, a shirt's neck should obviously not be too tight or too loose. If you have trouble breathing, it's way too tight. If it's mildly uncomfortable, it might be too tight, but be careful, because the next size up might be too loose. If it's falling away from your skin, it's probably too loose. So try on two sizes, and consider the possibility that neither works for you before committing to that brand. This is all less important if you don't plan to wear the shirt buttoned.

In terms of arm length, a long-sleeved shirt's arms should be visible under a tailored jacket, but only slightly.They should hit the end of the wrist, or, depending on your preference, slightly past there.

Wrist opening is not too complicated, but sometimes you may want your non-dominant hand to have a larger opening to accomodate a watch. MTM shirtmakers can do this.

Arm size is not too tricky, but some off-the-rack makers will have oversized, billowy arms to accomodate a large number of men. Don't go too slim, either, because that can restrict your range of motion.

Armhole opening is more important for comfort and range of motion than you might think. It's something MTM and Bespoke makers will recognize.

Sleeve pitch is worth considering. Essentially, if your sleeve always seems like it's twisted in some way, it might need to be turned at the shoulder by a tailor.

In terms of fit, you generally want a dress shirt to be fairly slim throughout the chest and body, down to the waist so it can stay tucked in neatly. Linen and rayon shirts are often better worn loose. For most other shirts, fit comes down to personal preference. A more relaxed fit can convey a soft, relaxed effect; a slim, trim fit can look more neat and put-together.

A casual shirt's length should generally reach about mid-fly, depending on how you wear your pants. you will often see this measured and referred to as back length, since it's easier to consistently measure from the back of the collar to the hem than from any other point on a shirt.

How to talk about shirt paraphernalia.

Collar stays, which I mentioned above, are the little flat things you put in a collar to keep the points pointy and stiff. They're okay.

Shirt stays are various doohickeys used to keep your shirt tucked in. Some of them work by weighing your shirt down, some (like "shirt garters") use elastic or clips, some involve tucking this into that, but from what I hear, none of them really work consistently. I wouldn't bother, and would instead, if you have trouble keeping your shirt tucked in, try for a better fitting shirt, or longer shirt, or higher rise trousers, or something like that.

Cufflinks are the things you put into the french cuffs described above. They are sort of jewelry, but unambiguously masculine. They can come in a few different forms, which I'll talk about in greater detail whenever I have a chance to update this article again.

Studs are somewhat similar to cufflinks, except they're used to secure the front placket of a tuxedo shirt, specifically.

Collar bars, collar pins, and collar clips are... bars, pins, and clips, usaully made of metal you either pin through or clip to your shirt collar, under your tie knot. These help give your tie and collar certain shapes that people like. Ethan Wong wears them with Spearpoint collars.

Alright, now which ones should I buy?

There are some affiliate links below, but I wouldn't recommend anything unless I believed in it.

Off the Rack / Ready to Wear.

Remember that fit is king, and that a shirt you can try on which does fit you is a better purchase than a shirt you can't try on that might fit you. Know a tailor. With that knowledge in hand, here are some brands I can recommend, in generally increasing price:

- Charles Tyrwhitt at their 3/$100 price.

- Spier and Mackay.

- Asket

- Portuguese Flannel

- SLOU, currently just doing seersucker popovers, but they're damn good.

- Jake's, particularly for OCBDs. Made to Order with custom sleeve lengths.

- Yeossal for polos

- Gitman Vintage

- Ring Jacket

- Turnbull & Asser

- 100 Hands

See, also, Eight Brands Making Unique, One-of-One Shirts For The Summer

Made to Measure.

Again, locality is important to fit, but for a new reason. Being measured in person by the company in question and having them available to remake or tailor your shirt in person are very valuable. Furthermore, being able to feel their fabrics in person also helps ensure a good fit. That said, here are some worthy brands:

Bespoke.

Picking a brand local to you is even more important here. Getting a shirt made bespoke requires that you be measured by the person who will cut the fabric, often more than once. It's possible to do this through trunk shows, but easier and more convenient to do this with a local tailor. That's often not a big brand, it's a small local business, and a person whose name you know.

All that said, here are a few brand names I can recommend anyway.

Special Thanks.

There's no way I'm going to remember everybody, but I'm going to try.

Thank you to Ethan Wong for helping explain some of the more confusing collars to me.

Thank you to Proper Cloth for providing an exceptionally large number of these photos.

Thanks to Reddit for sparking my interest in menswear and helping me learn most of this stuff.

And finally, thank you all for reading! This was a big effort for me, so I appreciate everybody who appreciated it!